Run DMCMC

Turning the geek factor up to 11 for a moment, there are some interesting possibilities for mathematical techniques used in technologies like predictive text to be used to assess fundraising interventions. Ever since an influential 1948 paper by Claude Shannon – “the Father of the Information Age” – so-called ‘Markov Chain’ models (a variant of which is ‘Markov Chain Monte Carlo’, or MCMC) have been “widely used in speech recognition, handwriting recognition, information retrieval, data compression, and spam filtering”, as well as ‘Natural Language Processing’/word prediction, by assigning probabilities to ‘state transitions’, ie the probability of one letter or word following another. Using such chains to predict which fundraising interventions are most likely to lead to a gift would be a huge boon for the industry, leading (in theory at least) to far more efficient donor journeys and more granular understandings of business process value. So, who wants to Run DMCMC?

Ratio’s(ination)

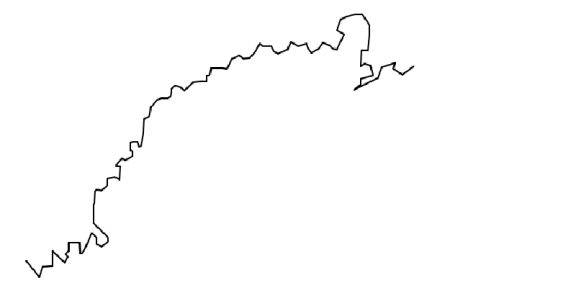

Imagine an ant crawling along a beach, left and right, forward and back, up and down, as it navigates home. It’s chosen path looks something like this:

The route is complex, but the complexity is a product of the environment, not the ant, whose decision-making power is minimal. The example is abstract but relevant for people, too: “human beings, viewed as behaving systems, are quite simple. The apparent complexity of our behavior over time is largely a reflection of the complexity of the environment in which we find ourselves.”

The question of how to navigate complex environments using limited decisionmaking capacity and incomplete information is at least as relevant for organisations as it is for animals. As a fascinating recent post [login required] to the Prospect-DMM email forum suggests, the answer may lie partly in the use of ratios, which offer an elegant, contextualised ways to cut through bewildering amounts of information. Simple, powerful metrics to use in fundraising could include:

- Last five years giving/lifetime total

- Responses/contacts

- Number of appeal/number of gifts

- Cost of appeals/lifetime donations

One obstacle is not being able to integrate or even extract information from our database systems to begin with. Recent news that insurance giant Aviva has made great strides in integrating database systems to the great advantage of their business raised a thought which is highly relevant for many charities: are we prisoners or masters of our IT/database systems? And, when techniques like database screening may be restricted or even off-limits in future, can we afford not to try to mine other data for insights?

Weapons of Math Destruction

If, as the ICO believes, the British public would experience “substantial distress” in learning their data had been processed in a wealth screening, the public will surely be distraught should they ever read Cathy O’Neils 2016 book Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. The many ways in which mathematical models and algorithms – the so-called ‘WMDs’ – are used to make crucial decisions relating to the public realm and, increasingly, private lives are as worrying and widespread as they are opaque and unaccountable. Across vital issues like criminal justice (where court decisions increasingly use automated quantitative modelling and scoring), access to credit, finance and education (where credit scoring and rating of teachers increasingly rely on WMDs), jobs and employment (where a missed payment could mean being overlooked for a job interview) and even the feelings and emotions we experience (thanks again, Facebook), WMD’s are in wide and growing use. This largely unseen trend is worrying as WMD’s inevitably contain errors and anomalies which, if not caught, can have significant effects for those affected by their scores or results. Even worse, WMDs can have pernicious effects when they run perfectly – many contain implicit value judgements which end up disadvantaging poorer groups, or, in the case of aggressive advertising, are designed to target these very people. Yet all too often WMDs’ methods and results go unchallenged.

O’Neils Mathbabe blog is an engaging mix of political commentary, engaging geekery and knitted hats – well worth a read. And both are valuable and timely in helping us to understand – and hopefully better manage – our algorithmic overlords.

Where is the Money (Going to Be)?

In No Country for Old Men, menacing assassin Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) shuns Woody Harrelson’s frightened offer of help to find a satchel loaded with millions of dollars. “I can find it from the riverbank”, a terrified Harrelson pleads at gunpoint, “I know where it is”. “I know something better”, counters the icy Chigurh, “I know where it’s going to be”.

As fundraising researchers, we spend a lot of time focusing on where the money is. But do we spend enough thinking about where it is going to be? The scene is a reminder that to prospect by relying on companies or sectors enjoying current success (as a way to assess employees’ affluence) is to miss a trick. Do we prospect often enough by trying to predict which sectors will become successful in the future? It may sound like a fool’s errand, but understanding which sectors and products are on a strong growth path and likely to experience an uptick in growth – wearable tech, virtual reality, voice recognition technologies and peer-to-peer finance come to mind – would be a boon for prospect research. Intelligence on mergers & acquisitions, IPOs and other comparable ‘liquidity events’ is equally valuable (lookin’ at you, Aramco). Such horizon-scanning need not be resource-intensive and is par for the course for many investors and businesses – for very good reason.

Calling Bullshit

How to call bullshit in the age of Big Data? There is now a whole course designed to do just that, and it is the best thing ever (no b*llshit).